Tool turns English to code

By

Kimberly Patch,

Technology Research NewsWriting software has been relatively difficult since people began programming computers in the mid-1900s. Although programming a computer is eminently useful -- it gives you fine control of a powerful tool -- it requires learning a programming language.

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology are aiming to remove this requirement. They have taken a step toward that goal with a language-to-code visualizer dubbed Metafor.

The visualizer uses natural language instructions to sketch the outlines of a program. It can be used as a programming learning tool and to provide rough drafts of programming projects, and could lead to more complete programming-by-natural-language methods.

Formal computer programming languages are difficult to write and inflexible, said Hugo Liu, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This makes them "quite a pain to debug and maintain," he said. "Hence the task of programming is rendered inaccessible to the general public."

Natural languages like English, on the other hand, are universally accessible, said Liu. "Natural language is so semantically rich and flexible that if it could be computationalized as a programming language, maybe everyone could write programs," he said.

At the same time, interpreting natural language is an extremely difficult artificial intelligence problem that is likely to take a decade or more to solve fully.

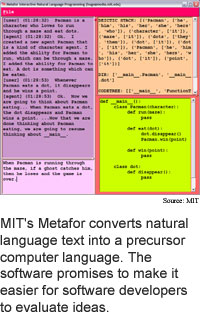

Metafor organizes a natural-language description of a program into the skeleton of a program by mapping the inherent structure of English -- parts of speech, syntax, and subject-verb-object roles -- into a basic programmatic structure of class objects, properties, functions, and if-then rules, said Liu.

While the logic of the researchers' interpreter tackles only about 20 percent of the problem of full natural language programming, it achieves about 80 percent of the perceived rewards, said Liu. "These code structures are a pragmatic implication of English syntax and semantics, but even these basic structures begin to resemble a nice program," he said.

The basic logic of the program Pacman, for instance, is revealed by talking about how it works, said Liu. "The basic ingredients for the program are there -- the noun phrases are objects, the verbs are functions, [and] the adjectives are object properties."

Metafor translates the description "Pacman is a character who eats dots" into a "Pacman object" that is a member of and can share traits, or functions, with a "character superclass" and has a character superclass member function of "eat dots", said Liu.

This is not the same as creating executable code, Liu added. "To visualize stories as code is not to create complete executable code, but rather it is to create scaffolding code which might be the highest-level skeleton of a program," he said.

In the researchers' study of seven intermediate programmers and six beginning programmers, subjects who saw their sentences translated into code this way were "seemingly quite surprised that all that information was contained in their utterance[s]," said Liu.

The study showed that brainstorming using Metafor made for faster completion of the programming task than brainstorming using paper, said Liu. Intermediates were about 10 percent faster and beginners 22 percent faster, according to the study.

The capabilities and limitations of the programmatic interpreter were also generally understood by participants, said Lui. "The first thing all the subjects [did was address] the aspects of visualized code which seemed wrong," he said. "Many subjects immediately identified the simplistic interpretation of the interpreter, and wanted the opportunity to rephrase their original wording to fix the error."

The most common reason for the apparent errors in the visualized code was the use of run-on sentences, which made it harder for the interpreter to organize the parts of speech as the user intended them, said Liu. Another key to conceptualizing programs is finding the precise verb.

Seeing language translated to logical code on-the-fly made the users more conscious of their communicative precision, said Liu. The subjects' quickly began using language that was simple and declarative, which, in turn, improved the usefulness of the system for brainstorming and outlining, he said.

To put together the program, the researchers wrote a parser that separates text into subject, verb and object roles, and programming semantics software that maps information from these English language structures to basic code structures. "The technical breakthrough [was] perhaps the discovery that there is a fairly simple mapping between shallow English syntactic-semantic structure and [object-oriented programming]-style programmatic structure," said Liu.

Metafor then uses this information to render skeleton code in any of several programming languages, including Python, Lisp and Java. Metafor renders code in real-time; the program shows the user four panels. As the user types one sentence at a time into one panel, the computer returns three panels of information: canned dialogue to confirm what the user said, debug information, and the code rendered into a programming language.

When a user mouses over a code object, an English explanation of the code is generated in pop-up window, said Lui. For example, the code describing a Pacman object with superclass "character", the property "color=yellow" and the function "eat(dot)" would evoke the generated text "Pacman is a character whose color is yellow and who can eat a dot."

The researchers' next step is to do a more extensive study of the way Metafor can assist students learning to program. "We... hope to add more sophisticated mixed-initiative dialogue so that the user can command the system to revise the visualize code, or the system might ask the user clarifying questions to clear up any ambiguities," said Liu.

The method could also be used as a system to teach kids programming by allowing them to play with stories and watch the results of their actions, said Liu. Metafor could also be used with massive multiplayer online games like Everquest and Multi-User Dungeons to allow any gamer to become a wizard capable of programming the gamer's space within that game world, he said. For instance, "I could program my own room by saying 'there is a brown room with lights in every corner, and a treasure chest in the center. If someone opens the treasure chest, the lights will all turn off.'"

The method could also be used to improve storytelling, said Liu. "An unverified intuition of mine is that precise storytelling and articulation are requisite skills for good programming ability," he added.

The program could be ready for practical use for brainstorming in less than two years, said Liu. It could be ready for educational purposes and integration with game worlds in three to five years, he said.

Liu's research research colleague was Henry Lieberman. They presented the work at the Intelligent User Interfaces Conference (IUI 2005) held January 9 to 12, 2005 in San Diego. The research was funded by MIT Media Lab sponsors.

Timeline: 3-5 years

Funding: University, Corporate, Private

TRN Categories: Programming Languages and Compilers; Data Representation and Simulation; Natural Language Processing

Story Type: News

Related Elements: Technical paper, "Metaphor: Visualizing Stories As Code," presented at the Intelligent User Interfaces Conference (IUI 2005) held January 9 to 12, 2005 in San Diego and posted at web.media.mit.edu/~hugo/publications/papers/IUI2005-metafor.pdf; Movie demo web.media.mit.edu/~hugo/demos/metafor-bartender-simple.mov

Advertisements:

March 23/30, 2005

Page One

Stories:

Tool turns English to code

Common sense boosts speech software

Inkjet prints human cells

How it Works: Biochips

Briefs:

Nanowires track molecular activity

Microdroplet makes mighty microscope

Cheap material makes speedy memory

Tiny crystals adjust laser colors

Electricity controls biomolecules

Nanotubes juice super batteries

Layers promise cheap circuits

News:

Research News Roundup

Research Watch blog

Features:

View from the High Ground Q&A

How It Works

RSS Feeds:

News

Ad links:

Buy an ad link

| Advertisements:

|

|

Ad links: Clear History

Buy an ad link

|

TRN

Newswire and Headline Feeds for Web sites

|

© Copyright Technology Research News, LLC 2000-2006. All rights reserved.