PCs

augment reality

By

Eric Smalley,

Technology Research NewsIf you're reading this story online, chances are you are looking at a desktop monitor and your hand is resting on a mouse. For years, researchers around the world have been working to eliminate the monitor and mouse.

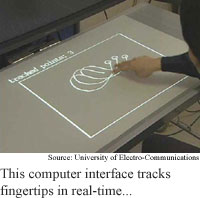

Using digital cameras, projectors, and software that tracks hands and fingers, several research teams have turned desktops into displays and fingers into pointing devices. These augmented reality systems blend real objects and digital information, turning a Web address on a printed page, for instance, into a clickable link.

But the systems generally use expensive, high-powered graphics workstations to handle the difficult task of recognizing and tracking fingers in real-time, which tends to limit augmented reality to venues like research laboratories and art exhibits.

A team of researchers in Japan has brought augmented reality to a standard PC by finding a way to track users' hands and fingertips that uses less computer power.

The researchers added an infrared camera to make it easier for their system, dubbed EnhancedDesk, to distinguish fingers amid the clutter of a desktop. The infrared camera sees heat, a hallmark of human skin. Display images projected onto a desk can sometimes overlap the users' hands, making even state-of-the-art computer vision techniques fail to detect hands and fingers in real-time, said Hideki Koike, an associate professor of information systems at the University of Electro-Communications in Japan.

They also gave the computer a little common sense. Ordinarily, if you instruct a computer to watch for fingers it will scan the entire arm looking for the telltale shape of a finger. The researchers' software knows to look for fingers only at the end of an arm, and to recognize that the semicircles at the ends of fingers are fingertips, which lightens the workload for the computer.

Armed with the knowledge of where a person's hands and fingers are, the system uses a standard camera that pans and tilts to follow the tip of the person's index finger as it moves around the desktop.

Users can put objects in the camera's field of view and tell the system what they are and what to do when someone points at them. When the system detects that a finger is pointing to one of these registered objects, it can, for instance, display related digital information that the person can then control with hand gestures, said Koike.

The idea is to allow people to read printed material and access accompanying digital information without having to use a keyboard or mouse to launch a program and find a Web page or multimedia file, said Koike. "In this environment, users [will] not need to be aware of the existence of computers," he said. "The system [will] automatically recognize what the users are doing by recognizing their gestures and objects on the desk."

The researchers have developed an educational program that works with the system. Interactive Textbook tracks the position and orientation of a textbook, recognizes certain pages and projects text, graphics, movies or Web pages at the appropriate angle and place on the desktop.

When students reading a physics textbook reach a page describing an experiment that shows the effect of a weight on a spring, for instance, the Interactive Textbook projects a simulation of the experiment to the right of the textbook. The students use their hands to control the simulation by moving or exchanging the weight and observing the effects on the simulated spring. "The students do not need to move their focus to using computers," said Koike.

EnhancedDesk is state-of-the-art, said Simon Baker, a research scientist at Carnegie Mellon University. "The complete system is very impressive. The [textbook] application is great," he said.

Augmented reality systems have a lot of potential, Baker said. "It is easy to imagine such tools being used in the very near future. [They] add a fun component to education, making the process far more enjoyable for kids," he said.

The one drawback to the system is the relatively high cost of infrared and pan-tilt cameras, said Baker. "It may... be possible to realize the basic idea using less expensive hardware," he said.

The researchers are adding a method for tracking a person's gaze, so the system can detect what a person is looking at, said Koike. The researchers' are also working on extending the system to whole rooms where it can track people's positions and project images on tables, walls and ceilings, he said.

EnhancedDesk could be ready for use in practical applications in a few years, said Koike.

Koike's research colleagues were Yoichi Sato of the University of Tokyo and Yoshinori Kobayashi of the University of Electro-Communications in Japan. They published the research in the current issue of the journal ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction. The research was funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture Sports, Science and Technology in Japan.

Timeline: 2-3 years

Funding: Government

TRN Categories: Human-Computer Interaction; Computer Vision and Image Processing

Story Type: News

Related Elements: Technical paper, "Integrating Paper and Digital Information on EnhancedDesk: A Method for Real-time Finger Tracking on an Augmented Desk System," ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, December, 2001

Advertisements:

June 26/July 3, 2002

Page One

PCs augment reality

Stamps bang out tiny silicon lines

Bent wires make cheap circuits

Mixes make tiniest transistors

Plastic computer memory advances

News:

Research News Roundup

Research Watch blog

Features:

View from the High Ground Q&A

How It Works

RSS Feeds:

News

Ad links:

Buy an ad link

| Advertisements:

|

|

Ad links: Clear History

Buy an ad link

|

TRN

Newswire and Headline Feeds for Web sites

|

© Copyright Technology Research News, LLC 2000-2006. All rights reserved.