Screen arcs widen view

By

Eric Smalley,

Technology Research NewsViewing a large map on a small screen can be frustrating, especially if you're trying to keep track of positions and distances of locations that fall far beyond the range of the screen.

Researchers from Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) have hit upon a simple solution that allows people to keep a sense of the relative distances of key offscreen locations. The software, dubbed Halo, was inspired by the arc of light that appears around streetlights.

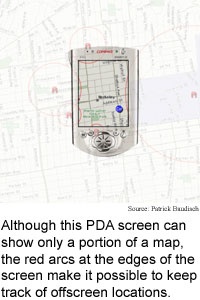

As a person navigates a map on a handheld computer, the software causes arcs representing selected offscreen locations to appear on the edge of the screen, as if the locations were surrounded by circles large enough that a portion of the arc just reached onto the screen. The user can sense how far away an offscreen location is by the curve and translucence of its arc, which indicates the size of the full circle and thus the distance to its center.

The software could make it easier to use small screens to navigate maps, three-dimensional environments, and keep track of moving targets like hazards, or even friends, according to Patrick Baudisch, now a researcher at Microsoft Research.

"Halo is a visualization technique that supports spatial cognition... by surrounding offscreen objects with rings that are just large enough to reach into the border region of the display window," said Baudisch. "Users can infer the offscreen location of the object at the center of the ring," he said. The arcs also become more translucent as they grow larger to give users a second distance clue.

The researchers hit on the idea while trying to use small dots at the window border to show distance. "Then I thought of street lamps and how they cast a halo of light onto the street," said Baudisch.

There are several other methods for providing offscreen information on small-screen devices, including overviews with detailed insets, fisheye views, and arrows. However, insets divide the user's attention, fisheye views distort distances and directions, and arrows fail to provide distance information, said Baudisch

The researchers tested their prototype software with 12 study participants who used it on a laptop and a relatively large handheld computer. The participants compared Halo and a second program that used arrows to point to offscreen objects.

The participants carried out four tasks: estimating where an offscreen object would lie in space, locating the closest of several offscreen objects, selecting five offscreen targets in the order that would form the shortest delivery path, and selecting a route to the closest of several on- and offscreen hospitals that would best avoid several on- and offscreen traffic jams.

The participants rated the difficulty of the tasks and the ease-of-use of the interfaces. The participants performed the tasks 16 to 33 percent faster, and a majority preferred the Halo interface for each of the four tasks, according to Baudisch.

Error rates were slightly lower for the Halo interface on the second, third and fourth tasks, but somewhat higher on the first task, even though 80 percent of the participants said they preferred Halo for that task. "The difference in accuracy was caused almost exclusively by subjects underestimating distances when using the Halo interface," said Baudisch.

The researchers are currently working to change the circles to ovals, which may allow people to perceive distance more accurately, Baudisch said. They are also working on a three-dimensional version of the software, he said.

The method could solve a potential problem in navigating complicated environments through a small handheld computer screen, according to Baudisch. "If I use... editing tools to move a graphical object around in [a] potentially infinite plane, how can I make sure I find it again?" he said. "Halo could... solve the problem."

The researchers are also working to adapt the method to real-time environments. "Halo gets really useful if offscreen objects move or change their relevance," said Baudisch. "Think of a handheld system that informs you about the availability of attractions in a theme park [or] hazards in a hostile environment."

On a handheld connected to a wireless network, halos could also represent the movements of people, for instance, the users' friends, Baudisch said.

The method is also appropriate for games, said Baudisch. "Think of a football game -- where are my teammates? -- is a player of the opposite team at a location where he or she could intercept my pass?"

The basic method is ready for practical use now, said Baudisch.

Baudisch's research colleague was Ruth Rosenholtz of Palo Alto Research Center. They presented the research at the Association of Computing Machinery Computer-Human Interaction (ACM-CHI) conference in Fort Lauderdale, Florida in April 5-10, 2003. The research was funded by PARC Inc.

Timeline: Now

Funding: Corporate

TRN Categories: Human-Computer Interaction

Story Type: News

Related Elements: Technical paper, "Halo: A Technique for Visualizing Offscreen Locations," presented at the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) Computer-Human Interaction (CHI) Conference 2003 Fort Lauderdale, Florida April 5-10, 2003, and posted at www.ipsi.fhg.de/~baudisch/Publications/2003-Baudisch-CHI03-Halo.pdf.

Advertisements:

May 7/14, 2003

Page One

Screen arcs widen view

Light show makes 3D camera

Net scan finds like-minded users

Sound forms virtual test tubes

News briefs:

Nanotube shines telecom light

Touchy-feely goes remote

Light mix makes strong metal

Metal expands electrically

Researchers fill virus with metal

Gold connectors stretch

News:

Research News Roundup

Research Watch blog

Features:

View from the High Ground Q&A

How It Works

RSS Feeds:

News

Ad links:

Buy an ad link

| Advertisements:

|

|

Ad links: Clear History

Buy an ad link

|

TRN

Newswire and Headline Feeds for Web sites

|

© Copyright Technology Research News, LLC 2000-2006. All rights reserved.