PC

immortalizes ancient temple

By

Ted Smalley Bowen,

Technology Research NewsThe business of studying past cultures has come a long way since the days when scenes of pith-helmeted Western explorers bagging historical trophies were immortalized in sepia-toned photos.

In addition to a generally higher level of cultural sensitivity, excavations are less damaging to the sites, and collecting digital data allows researchers to follow up their fieldwork without carting objects home with them.

Given the many threats to archeological sites -- development, looting, war, pollution, and time -- there's an urgency to capturing three-dimensional images of them and archiving the material in a lasting medium.

State-of-the-art methods use laser-guided measurement tools, memory-hungry graphics, and supercomputer-strength data analysis. But the sheer number of sites, many of which are in less affluent countries, dictates that cheaper, off-the-shelf configurations will have to do much of the work.

A researcher from the University of Calgary has shown that it is possible to capture a lot with computers that are considerably less than state-of-the-art.

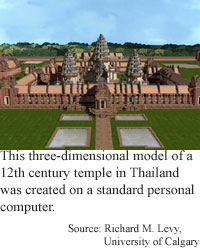

Richard M. Levy, an associate professor of urban planning and environmental design, has made a computer model of a 12th century Khmer temple complex in Phimai, Thailand using a last-generation Pentium 3 running at 733 megahertz with a fairly modest 512 megabytes of memory, standard video card, and 32-megabyte graphics chip. The set-up can be had for well under $3,000, according to Levy.

The reconstructed complex, a United Nations World Heritage site, includes temples, libraries and ancillary structures.

Balancing the needs of scholars, who want the most accurate and detailed data possible, with the need to get the information to the public, Levy used a couple of shortcuts to do the job with his off-the-shelf computer equipment.

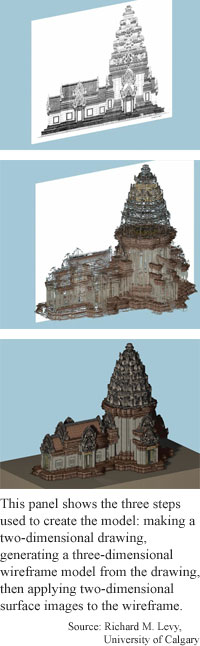

He used site and elevation maps to generate two-dimensional images and three-dimensional frames of the buildings. Rather than model each stone block and building detail individually, he used images of entire surfaces to fill out the frames.

This allowed him to produce the three-dimensional images using much less computer time. The trade-off is the less detailed model is not as good for scholarly use. It would, however, allow academics to analyze structural properties and possibly establish what materials might have been used originally, or to figure out how to reconstruct a site, said Levy.

He also varied the level of detail, displaying foreground images most sharply and shrouding the middle-ground and background in a convenient fogbank.

The model still used 200,000 polygons, so Levy programmed the simulation so that fewer than a third of the 3-dimensional polygons would be rendered at any given time.

This raised the frame rate of the simulation to eight or ten frames a second, which made a viewable virtual video. From this he made a QuickTime virtual panorama of the site, which can be viewed over the Web and with any system running the common QuickTime viewer.

Virtual representations of antiquities have many clear-cut uses. They add multifaceted documentation to the historical record, far surpassing grainy black-and-whites and jumpy film or video images. They also make effective teaching tools and can vastly expand the audience for all forms of archeological perusal, according to Levy.

One of the goals of the project is to raise awareness about the sites and push authorities to enact protections, he said. "We're hoping virtual tourism will be helpful in areas where people don't have monuments in their complete states."

Virtual representations also allow researchers, museumgoers, tourists and students to view a potentially limitless number of site re-creations without disturbing any actual artifacts. "It's possible to destroy them in the process of [physically] rebuilding them," said Levy.

One remaining question, however, is whether a virtual model will satisfy tourists, he said. Web sites may allow tourists to examine a place without traveling, but "are they still going to want to see the real thing?"

The medium raises other issues for digital preservationists and scholars. A formal method for reconstructing archeological sites virtually is needed, but is difficult to hammer out because data capture, archival and presentation technologies are all in flux, Levy said.

At the same time, there is pressure to simply capture the data as soon as possible, regardless of format. Financial considerations also restrict standards, especially because there is great discrepancy in funding worldwide, he said.

The Phimai project also made clear a key problem in trying to serve both the scholar and the general public from a single model generated on a low-cost PC: today's software cannot meet both the scholar's need for accuracy and detail, and the museum, tour and school crowd's interest in a satisfying virtual tour, Levy said.

This is because the CAD and GIS software that links geometric details to extensive databases of information and allows new artifacts to be easily added and cataloged does not render images very realistically. This means making separate models for archeological site surveys and for realistic virtual reconstructions, said Levy.

Despite its drawbacks for researchers, Levy's model "is clearly visually stunning;" he has produced "very nice results" considering the tools he used, said Scot Thrane Refsland, director of research and Development at the center for Design and Visualization at the University of California at Berkeley. The work has advanced the industry by raising the quality of this type of model, he said. "Dealing with the performance versus accuracy issues... is a difficult line to straddle. Dr. Levy seems to have nicely balanced the two to gain acceptable performance and accuracy for both the technologist and the archaeologist."

The work is ďa great starting point for site managers of historical locations to find out how to best approach the daunting task of building a virtual heritage model," he added.

It also highlights tensions between the main constituencies interested in virtually preserving archaeological sites, Refsland said. "Artists want creative freedom, and historians want the truth. One of the dangers of virtual heritage is that every built virtual environment is going to be the artistic interpretation of the people constructing it, no matter how much effort is put into accuracy," he said.

Other potential projects include representations of the Khmer site at Angkor Wat in Cambodia, sites in northern Canada, and a model showing Calgary throughout the past century, Levy said.

Levy is scheduled to present the work at the 7th International Conference on Virtual Systems and MultiMedia in Berkeley, California, Oct. 25-27, 2001. It was funded by the Multimedia Advanced Computational Infrastructure project and the Canadian International Development Agency.

Timeline: Now

Funding: University, Government

TRN Categories: Applied Computing; Data Representation and Simulation; Graphics

Story Type: News

Related Elements: Technical paper, "Temple Site at Phimai: Modeling for the Scholar and the Tourist," 7th International Conference on Virtual Systems and MultiMedia, Berkeley, California, Oct. 25-27, 2001; Web site http://www.phimai.ca.

Advertisements:

October 24, 2001

Page One

DNA could crack code

Transistor sports molecule-thin layer

Molecule connects contacts

PC immortalizes ancient temple

Laser boosts liquid computer

News:

Research News Roundup

Research Watch blog

Features:

View from the High Ground Q&A

How It Works

RSS Feeds:

News

Ad links:

Buy an ad link

| Advertisements:

|

|

Ad links: Clear History

Buy an ad link

|

TRN

Newswire and Headline Feeds for Web sites

|

© Copyright Technology Research News, LLC 2000-2006. All rights reserved.