Skulls gain virtual faces

By

Kimberly Patch,

Technology Research NewsWhen police find a skull and want to know what its owner looked like, they generally use artists who reconstruct the face by building up layers of clay over the skull.

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Computer Science in Germany have advanced efforts to computerize the process.

The method could speed forensic work, and could also be used to reconstruct long-extinct animal species, said Kolja Kähler, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute.

The idea came about when the researchers used an anatomy-based approach for facial modeling and animation. "One of the major problems there was shaping... anatomical structures to fit a given 3D skin model," said Kähler. The researchers later realized that the method could be inverted. "Using just about the same math, it is also possible to start from a virtual skull model and construct the muscle layer and skin on top of that," he said.

When they examined existing manual facial reconstruction methods, the researchers found that their method was "essentially the virtual counterpart to the de facto standard method used for manual facial reconstruction in police work," said Kähler.

There are two manual reconstruction methods. The anatomical method builds layers of muscles, glands and cartilage over the skull, then adds a skin layer. The second, faster method uses a set of average tissue thickness measurements to build up a face. The first method takes hundreds of hours, requires in-depth anatomical knowledge, and is more often used to reconstruct fossil faces. Where statistical data about a population -- like modern humans -- exists, the second method is more often used.

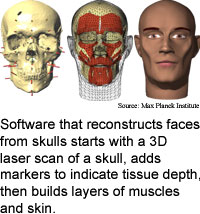

The researchers' software allows users to attach markers, or landmarks, to a three-dimensional skull model generated from a laser scan of a skull. The landmarks are correlated with statistical tissue depth measurements in order to provide reference points for the software to generate muscles and skin for the model.

An existing technique selects a computer-generated face from a database of faces and warps it to match the depth markers from landmarks on a skull. The researchers' approach, in contrast, has only one starting template and requires fewer landmarks, according to the researchers.

The model's virtual muscles control its animation. The muscles are connected to the skull and skin, and when muscles move, they also change the skin layer. The model can be edited by changing the location of the landmarks.

The method also includes rules that determine traits like the width of the nose and the position of the nose tip. The width of the mouth, the thickness of the lips, and the parting line between the lips are all determined by the size of the front few teeth.

The method is much faster than manual techniques, and can easily produce alternate models and different facial expressions, according to Kähler. It takes less than a day to make a computer reconstruction compared to weeks for a traditional clay model. Using the computer method, different facial expressions or slimmer or heavier versions of the face can be produced within seconds, according to Kähler. Because the clay methods are time-consuming, it is usually not practical to make alternate models.

The researchers' method works as well as the manual tissue depth method, according to the researchers.

The researchers' next step is collaborating with anthropologists and forensic artists to make the method practical, according to Kähler. "We have already established cooperation with the Institute for Forensic Medicine at Saarland University," he said.

The method is a clever combination of existing technologies, and is useful work, said Martin Evison, a senior lecturer in forensic and biological anthropology at the University of Sheffield in England. "It would be good to have a practical method of reconstructing the face from the skull by computer in forensic cases," he said. "Clay sculpture is time-consuming and can require considerable artistic talent."

The current prototype figures o suffer a problem common to computer-generated faces, said Evison "They look ridiculously mannequin-like."

Kähler's research colleagues were Jörg Haber and Hans-Peter Seidel. The researchers presented the work at the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) Special Interest Group Graphics (Siggraph) 2003 conference held in San Diego July 27 to 31. The research was funded by the Max Planck Institute for Computer Science in Germany.

Timeline: Now

Funding: Institute

TRN Categories: Data Representation and Simulation; Graphics

Story Type: News

Related Elements: Technical paper, "Reanimating the Dead: Reconstruction of Expressive Faces from Skull Data," slated to appear in the proceedings of the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) Special Interest Group Graphics (Siggraph) 2003 conference held in San Diego July 27 to 31.

Advertisements:

August 13/20, 2003

Page One

Skulls gain virtual faces

Viewer explodes virtual buildings

Tool blazes virtual trails

Quantum computer keeps it simple

News briefs:

Video keys off human heat

Interference boosts biochip

Device simulates food

Motion sensor nears quantum limit

Molecule makes ring rotor

Carbon wires expand nano toolkit

News:

Research News Roundup

Research Watch blog

Features:

View from the High Ground Q&A

How It Works

RSS Feeds:

News

Ad links:

Buy an ad link

| Advertisements:

|

|

Ad links: Clear History

Buy an ad link

|

TRN

Newswire and Headline Feeds for Web sites

|

© Copyright Technology Research News, LLC 2000-2006. All rights reserved.